The Zwinglian conception of Christian salvation is linked to a form of humanist universalism of the Spirit that contrasts with the usual conceptions of the Reformation, but which echoes a certain reading of the epistle to the Romans. Here are a few points of reference on the subject.

1 Zwingli, father of the Reformation

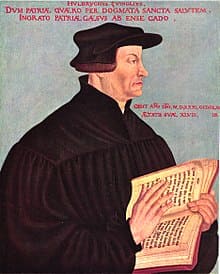

Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) was the father of the Swiss Reformation and of the so-called “Reformed” branch of the Protestant Reformation (which is conveniently divided into Lutheran, Reformed, Radical and Anglican*).

A contemporary of Martin Luther, he shared many of Luther’s views and was undoubtedly influenced by them, but the two men also clashed sharply, particularly over the question of the Lord’s Supper.

2 Erasmian and humanist

A disciple of the Dutch Catholic humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, Zwingli was also a humanist whose relationship with the philosophical heritage of the Ancients was profound and complex, and explains the importance of reason in his theological thinking, whereas Luther regarded it with more suspicion, referring to it as ‘the devil’s whore’.

This perhaps explains Zwingli’s constant effort to integrate a reflection on the human condition in general with the Protestant problem of salvation by justification through grace, the central doctrine of Lutheran thought.

3 The universalism of the Spirit

In his early days, Zwingli was first and foremost a moralist, preaching the demands of the Gospel in the optimistic spirit of Erasmian humanism. And although the failure of this approach and the discovery of Luther’s thought led him to temper this optimism and amend his point of view by taking into account the weight of sin in man’s depravity, he nonetheless retained an original conception of the work of the Spirit.

For him, “the Spirit imprints the demands of the divine law “** on the heart of every man, Gentile or Jew, Christian or not, and the “good and virtuous” pagans who do not know Christ have access to salvation themselves, even if they also owe it to the redemptive work of the Nazarene.

In this, Zwingli is undoubtedly only echoing the Apostle Paul in Chapter 2 of the Epistle to the Romans, but he is initiating a genuine “spiritualist universalism”** that is absent in Luther and in his successor Jean Calvin, which perhaps foreshadows that of Friedrich Schleiermacher, the father of liberal Protestantism.

–

Sources

*A. Gounelle, Huldrych Zwingli, La foi réformée, Olivétan, 2000.

**J.V. Pollet, Huldrych Zwingli et le zwinglianisme, Vrin, 1988.

0 Comments