The doctrine of the trinity or tri-unity is emblematic of Christian theology, and is one of the elements of the tradition largely taken over from the Protestant Reformation. Here we present biblical, conceptual and historical elements that enable us to reconstruct a synthetic account of this touchstone of Christianity, adopting a ‘dynamic’ point of view that gives pride of place to a theology of the Spirit.

Introduction: Trinitarian theology and Christology

Conceiving a tri-unity to understand Christ

Christians confessed the divinity of Jesus Christ quite early on, in particular by taking up the statements in Scripture that make him the “Son of God”. One of the most famous of these is found in the Gospel according to Matthew:

When Jesus came to Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, “Who do people say that I am, the Son of Man? They replied: Some say you are John the Baptist; others, Elijah; others, Jeremiah, or one of the prophets. And you,” he said to them, “who do you say that I am? Simon Peter answered, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God. Jesus answered and said to him, “Blessed are you, Simon, son of Jonah, for flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven.

Gospel according to Matthew, Chapter 16, verses 13 to 17

So, in Christ’s own words, to confess him as “Son of God” is to receive God’s own revelation of his identity. But how are we to think about this affirmation? How can God, who is “spirit”, have a Son? As we shall see, the answer lies in attributing divinity to Jesus Christ himself in the Gospel according to John.

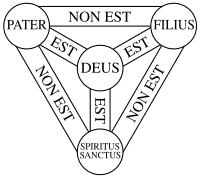

Now, in order to give meaning to this divinity without undermining the uniqueness and identity of the Christian God, and without identifying Jesus Christ with the one whom Scripture calls the Father, ancient theologians invented and developed the concept of the ‘Trinity’ or ‘Tri-unity’. This idea, which can be summed up succinctly as “God is One and subsists in Three Persons”, initially emerged from Christological considerations, i.e. those relating to the doctrine or complex dogma of Christ (Councils of Nicaea I, (where the divinity of the Son is affirmed) and Chalcedon (where the dual nature of Jesus Christ is conceptualised)). There are in fact several complementary and paradoxical assertions in Scripture about the relationship of Jesus Christ to God, and thanks to the resources of ancient philosophy, ancient theologians gradually and painstakingly developed their understanding of God himself in order to understand Jesus Christ.

The historical contribution of ancient theology and biblical exegesis

As we look back over twenty centuries of Christianity, we benefit from this ancient effort, even if we don’t always know it or recognise it. Although the elements of the Trinitarian and Christological doctrines are to be found in Scripture, it is far from the case that these doctrines themselves are articulated there, not to say formulated, as they are in the rest of Christian tradition, and in the form in which we confess them today. We believe that this ancient work has therefore been eminently and universally profitable, and that we can embrace its main conclusions for confessing and thinking about the Christian faith even today.

We will begin by setting out the classical Trinitarian doctrine, showing that it is supported by Scripture, and opting for a dynamic rather than static conception of the Trinity, insisting on the living relationships between the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, thanks to additions that are part of a genuine theology of the knowledge of God. We will present biblical and historical texts that form the basis of the classical understanding and the relationship between Trinitarian theology and Christology: the biblical text will come before ancient dogmatics, Trinitarian theology before Christology proper, and in particular the doctrine of the Incarnation, which we will deal with later.

1 The eternal One and Many

Trinitarian theology is interpreted in the context of the ancient problem of the “One and the Many”, i.e. which comes first, the One or the Many, in other words which proceeds from the other? Cornelius Van Til repudiated the doctrine of the Greek philosopher Parmenides (as expounded in Plato’s discourse of that name), in order to affirm the ‘co-terminality’ of the eternal One and Many in God, which is a bold reinterpretation of classical Trinitarian theology, and also to affirm the co-terminality of the created One and Many.

1.1 The One-Many duality in the Old Testament

When we introduced the biblical God as the eternal creator of the universe and of man (see God the Creator of the Universe), we mentioned the distinction in God between a fundamental unity and a fundamental multiplicity, reflected in particular in the creation of man (see also Man, a creature of God). But the story of man’s creation is not the only place in the Old Testament where this “duality” is expressed. Perhaps the clearest indication of multiplicity in God is found in the many references to the “angel of the Lord”, the manifestation of a person both distinct from God and identified with God himself. This entity, for example, intervened on several occasions in the lives of Abraham and those close to him (notably in Genesis 22:11, when he stopped Abraham’s hand as he was about to sacrifice his son Isaac). Although the expression sometimes refers to an angel sent by the Lord, on other occasions God himself appears to be referred to in this way. For example, when God appears to Moses in the burning bush, it is as “the angel of the Lord”:

Moses was feeding the flock of Jethro, his father-in-law, priest of Midian; and he led the flock behind the desert, and came to the mountain of God, to Horeb. The angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire in the middle of a bush. Moses looked, and behold, the bush was all on fire, and the bush was not consumed. Moses said, “I want to turn aside and see what this great vision is, and why the bush is not consumed. When the Lord saw that he turned aside to see, God called him from the bush and said, “Moses! Moses! And he said, Here I am.

Exodus, Chapter 3, verses 1-4

The appearance is that of the angel of the Lord, the voice is that of God himself: even if the angel of the Lord and God are not explicitly identified here, how could what Moses sees and what he hears not correspond? Another Old Testament text is particularly explicit:

Then the angel of the Lord came and sat under the oak of Ophrah, which belonged to Joash, of the family of Abiezer. His son Gideon was threshing wheat in the wine press to keep it safe from Midian. The angel of the Lord appeared to him and said, “The Lord is with you, you valiant hero! Gideon said to him: Ah, my lord, if the Lord is with us, why have all these things happened to us? And where are all these wonders that our fathers tell us about, when they cry out: Did not the Lord bring us up out of Egypt? Now the Lord has abandoned us and given us into the hands of Midian! Then the Lord turned to him and said, “Go with all your strength and deliver Israel out of the hand of Midian; have I not sent you?

Judges, Chapter 6, verses 11-14

Once again, the angel of the Lord, who addresses Gideon in an apparition, is identified with the Lord himself. So the ancient Israelites were familiar with this kind of expression of the multiplicity intrinsic to the divinity, suggested as early as the creation story, and declined in this type of allusion.

1.2 The One-Many duality in the New Testament

1.2.1 The Logos

This duality of the One and the Many in God is taken up again in a clearer and more explicit way in the New Testament. The fundamental text we are referring to in this respect is found in the prologue to the Gospel according to John:

1 In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God.

Gospel according to John, Chapter 1, verses 1-3

2 In the beginning he was with God.

3 All things were made through him, and without him nothing was made that has been made.

We have preferred to translate “ho logos” (Greek ὁ λόγος) as “the Logos” rather than “the Word”, so as not to take too strong an option as to the meaning to be given to this word, and because “Logos” is an essential philosophical and theological concept that we want to preserve and reinvest. The fourth Gospel opens with an obvious Christian reworking of the biblical Genesis account: while God created the world by his “word” – an expression of his will – the apostle reinterprets this tradition by making the “Logos” (verse 3) the agent of creation, the vehicle of the divine word. In so doing, he introduces a “middle term” between God and the created universe, this Logos of whom he tells us in both verses 1 and 2:

1) That he “was with God” (or “with God”), which distinguishes him from God by situating him in relation to the latter, with the help of a verb in the imperfect tense, which therefore expresses continuity, in this case a permanent state

2) That he “was God”, with an inversion of the syntax, literally “(it is) God (that) the Logos was”, according to a construction which typically places the emphasis on the attribute, here “God”, to insist on the identity of the Logos with God

3) That he “was in the beginning with God”, and therefore that he pre-existed the creation of all things, which, moreover, were made by him (verse 3).

The apostle John thus presents Jesus Christ to us through the Logos, the agent of the creation of the world and pre-existent to all things, assimilated to God himself and yet distinct from him. In this metaphysical scheme, we have the affirmation of an apparent contradiction, what we call a paradox: if the Logos was close to God, then he was distinct from God; if the Logos was God, then he was not distinct from God. As with all paradoxes, the resolution of this one requires further reflection on the concepts involved, based on the exegesis of other biblical texts (several of which are in the same gospel) and on philosophical creativity (which inevitably takes place outside the biblical text stricto sensu).

1.2.2 The Father and the Son

If the prologue of the Gospel according to John leads us to distinguish paradoxically “between God and God” with the introduction of the Logos, the same text introduces a first element of solution to the paradox raised, by distinguishing in God two distinct modalities:

14 […] The Logos was made flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; and we beheld his glory, a glory like the glory of the only Son from the Father.

Gospel according to John, Chapter 1, verses 14-18

15 John gave witness to him, and said, This is he of whom I said, He who comes after me has gone before me, for he was before me.

16 And from his fullness we have all received grace for grace;

17 For the law was given by Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ.

18 No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, is the one who has made him known.

These ineffable words introduce a transformation of the language used: the “Logos”, the metaphysical reality, the agent of creation (and sustenance, see Colossians 1:15-17 and Hebrews 1:1-4 for example) of the universe, “became” a man (verse 14: we will come back to this when we deal with the Incarnation), who manifested the glory of the only-begotten Son who came from the Father (ibid.). This man is precisely Jesus Christ (verse 17), who made God known as “the only Son who is in the bosom of the Father”. It is by distinguishing in God between a Father and a Son that the paradox must be resolved: the Logos or Son “was” with God as being “in the bosom” of the Father; he himself was God as being his “only Son” who is in his bosom. In other words, God is Father and has a Son in himself, who is also God.

This reformulation of Johannine thought still does not provide us with concepts with which to form a “theory of God”. But by assembling various elements of the text, it introduces the idea that there is a complex “structure” in God, which makes it possible to account for the assertions about the Logos, and which is revealed to us here so that we can understand Jesus Christ, and his relationship to God and to ourselves. Here, to go further, we would have to introduce a concept to think about this “structure” of the divinity, and this is the path followed by the old conciliar theology. For the moment, following the famous Swiss theologian Karl Barth, we could be content to speak of modality: the biblical God, who is one, but who has also been known as mysteriously multiple since the Book of Genesis, subsists in two distinct modalities, the Father and the Son. The notion of modality is appropriate for the time being, since it connotes that the same God is both Father and Son: the Logos or Son refers to a modality of the same divinity, which is why he can be called God, and himself situated next to God, if the latter is understood this time as the Father.

1.2.3 The Holy Spirit

If the Father and the Son are conceived as two modalities of the same God, the chosen words connote and recall God’s personality (see the God creator of the Universe), and notably His thought and His will. Yet, the same gospel introduces a third modality of divinity in the Spirit. The word literally means “breath,” and thus seems to refer to an impersonal element, which therefore should not a priori be considered as a modality of the personal God. However, personal attributes are attributed to him, as for example in Chapter 15 of the same gospel:

13 “But when the Comforter is come, the Spirit of truth, he will guide you into all truth: for he shall not speak of himself; but whatsoever he shall hear, that shall he speak: and he will show you things to come. 14 He shall glorify me: for he shall receive of mine, and shall show it unto you. 15 All things that the Father has are mine: therefore said I, that he shall take of mine, and shall show it unto you.”

Gospel according to John, Chapter 15, verses 13-15

This is not enough to affirm that the Spirit is a modality in which God subsists in the same way as the Father and the Son, but it is enough to attribute to Him, by analogy, the same personal character: we discern in the Spirit an intention, a will, an expression, a centered action. The identification of the Spirit as a third modality in God also relies on other fundamental texts, of which the main one, which we find in the first epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, allows us to articulate the distinct concepts of Logos and Son:

9 “But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him. 10 But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God. 11 For what man knoweth the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? Even so the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God.”

1st Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, Chapter 2, verses 9-11

The Spirit is here thought by the Apostle Paul as autonomous, probing everything that is in God, and revealing to men what is of His knowledge. He is the one who knows God in “his depths,” since he “searches” him, and is therefore not a mere “force” that emanates from God: he can therefore be the one who announces what is to the Father, and therefore to Christ, to the disciples (Gospel according to John 15,13-15, op. cit.).

2 A dynamic conception of the Trinity

To speak of God, we prefer to speak of subsistence rather than existence: God “subsists” as he is, but the term “existence”, even if it is appropriate in its current usage, etymologically refers to the idea of “being outside of”: now God is not outside of anything, and even all things “subsist in him” (Epistle to the Colossians, Chapter 1, verse 17). Thus, if God subsists in three ways, the Holy Spirit – the word “Spirit” meaning “breath”, let us remember – refers to the very dynamic of God’s infinite life, to the point where Christ can characterise the very essence of God as “spiritual”:

[But] the hour is coming, and has already come, when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and in truth; for these are the worshippers the Father requires. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth.

Gospel according to John, Chapter 4, verse 24

Now, the essence of God as spirit provides the key to a dynamic conception of divine being, articulating the concepts of the Logos – as the expression of God in himself – and the Son – as the begotten of God in himself. To take an image, God is a source (the Father) whose flow (the Spirit) flows into himself (the Son).

2.1 The ontological precession of God as Father

The source of the divinity is the person of the Father, i.e. God, as he subsists in himself in the foundation of his being. This establishes not a hierarchy, but a “predisposition”, in the sense that the Father comes before the Son and the Spirit, not in a chronological sense, but in an ontological sense (relating to being). This is perhaps why God and the Father are frequently identified in the New Testament, in the prologue to the Gospel according to John for example, where we have noted that if the Logos is the Son, then the Father is “God” with whom the Logos was in the beginning (John 1:1, op. cit.). This does not exclude the full divinity of the Son and the Spirit, but emphasises the identification of the Father with the fundamental being of God, as we invariably read in the addresses of the Pauline epistles, where the Son is equated with the Lord, which does not detract from the “lordship” (i.e. dominion) of the Father either:

Paul, called to be an apostle of Jesus Christ by the will of God, and the brother Sosthenes, to the Church of God which is at Corinth, to those who have been sanctified in Jesus Christ, called to be saints, and to all who call on the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, their Lord and ours, in any place: grace and peace be to you from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

1st Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, Chapter 1, verses 1-3

The “Father” here is certainly “our Father”, and therefore defined in relation to men; but the assimilation of the Christian to Jesus Christ by divine adoption places him on a level analogous to the Son of God in relation to God the Father. The identification of God with the Father is also explicit in the same epistle, where we read about “idols”:

[…] If there are beings who are called gods, whether in heaven or on earth, just as there are many gods and many lords, nevertheless for us there is only one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we are, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we are.

1st Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, Chapter 8, verses 5-6

This magisterial text clearly identifies God and the Father, among all the “divinities”, without taking away the divinity of Jesus Christ, since it is through him that “all things are”.

2.2 Expression of the Logos and begetting of the Son

The essential ontological distinction between God and the universe is that God derives his being only from himself (he subsists in and through himself), whereas the universe or creatures derive their being from God (they subsist in and through him). Theologians speak of aseness to designate this characteristic attribute of the divinity. Thus, God has no part in creation or becoming and is therefore immutable, but his eternal subsistence in himself does not mean that God must be conceived in a “static” way. As we have emphasised, in the Spirit there is a movement by which God knows himself completely: we affirm that the expression of this knowledge of God in God is the Logos, and that this movement is eternal, i.e. perpetual, and constitutes the very life of God. The symbolic vocabulary used allows us to posit that just as the breath carries the word, the Spirit carries the Logos, which is therefore the result of what the Spirit produces in God, the knowledge of God by itself. As the expression of God the Father in himself through the movement of the Spirit, the Logos is therefore also the Son, which the image of begetting expresses in another way: the Son is produced by the life of the Spirit in God, he is therefore begotten. Thus, in God, the expression of the Logos and the begetting of the Son are one and the same thing, the result of the “process” constituted in God by the movement of the Spirit, through which he knows himself. The notion of knowledge in God is therefore fundamental and constitutive of his very being. The theologian Cornelius Van Til also spoke of the co-terminality (see the section on the Eternal One and Multiple) of being and knowledge in God: God’s being and the knowledge he possesses of himself are co-terminal.

2.3 The life of God and the persons of the Trinity

The Spirit is thus God as he subsists in the movement by which he knows himself and expresses himself integrally in himself. We thus have here a dynamic conception of the Trinity, since the three modalities or persons in which the same God subsists are structurally linked by the divine life, which is a movement, not a static reality. According to this conception, God is the Father, the Son is God in that he “has become himself” and the Spirit is God in that he “becomes himself”, but these analogies must be understood as denoting a process that is both eternal and eternally completed, constitutive of the being of God himself. The dynamic character of the structure of divine being is, moreover, consistent with Johannine theology, which makes ‘life’ a central element of the divinity and its manifestation, as we read in the Gospel according to John:

In him [the Logos] was life, and the life was the light of men. The light was in the darkness, and the darkness received it not.

Gospel according to John, Chapter 1, verses 4-5

and in the first epistle of John :

What was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life – for the life has been made manifest, and we have seen it and bear witness to it, and we proclaim to you eternal life, which was with the Father and has been made manifest to us – what we have seen and heard we proclaim to you, so that you too may have fellowship with us. And our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ.

First Epistle of John, Chapter 1, verses 1-3

3 History of the Trinitarian dogma

Numerous other biblical texts explicitly associating the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit in the same God support this idea of the subsistence of God in three distinct modalities or persons. However, the order of this biblical and conceptual presentation has so far ignored the genesis of the Trinitarian doctrine in Antiquity, which is not explicitly formulated in the biblical text itself, but was subject to progressive elaboration, on the occasion of several Christological controversies (dealing with the doctrine of Christ).

3.1 The First Council of Nicaea (325)

This Council, a meeting of bishops from the ancient Catholic Church, was the first to be considered “ecumenical”, i.e. representing the universality of the Christian Church. It was convened by the Roman emperor Constantine I, and its purpose was to settle controversies dividing the churches, principally a dogmatic issue concerning the nature of Christ between the priest Arius of Alexandria and his bishop Alexander, a dispute that could not be resolved diplomatically. Arius had first argued that Christ was a creature of God, then that he had been begotten of God, but in the form of a creation. He was condemned by Alexander, but supported in particular by Eusebius of Nicomedia and Eusebius of Caesarea. The discussions at the council were not enough to bring the protagonists to an agreement, and the Arian theses were condemned by a large majority. The summary of the dogma adopted at the first Council of Nicaea has come down to us in the form of a confession of faith, the Nicene Symbol, the translation of which we reproduce here:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, creator of all visible and invisible beings. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, born of the Father, that is to say, of the substance of the Father, God of God, light of light, true God of true God; begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father, by whom was made all things in heaven and on earth; who for us men and for our salvation came down, was incarnate and became man; suffered, rose on the third day, ascended into heaven, and will come again to judge the living and the dead. And to the Holy Spirit. The Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematises those who say: “There was a time when he was not, before he was born he was not; he was made like the beings drawn from nothing; he is of a different substance (hypostasis), of a different essence (ousia), he was created; the Son of God is mutable and subject to change”.

The Nicene Creed (Wikipedia, 20/08/2022)

However provisional the wording of the symbol may be, it is remarkably elaborate and already conceptually very precise, demonstrating the genius and philosophical technicality of its designers and writers. A number of elements, already mentioned in the previous sections, which take up and complete the assertions of the biblical text, make it possible to order them into an initial coherent doctrine. The uniqueness of God, identified as Father, is explicitly stated. The uniqueness of Jesus Christ as Lord, noted in the addresses of the Pauline epistles, is also affirmed. The relationship of Jesus Christ to God is expressed as that of Son to Father, according to a relationship not of creation but of begetting in God, the Son being said to be “born of the substance of the Father” and therefore “consubstantial” with him, thus being with him one and the same God, sharing one and the same substance (hypostasis) and one and the same essence (ousia). The totality of the works of creation is attributed to the Son as well as to the Father, as in the prologue of the Gospel according to John. The confession of the Holy Spirit does not contain any details, but it is worth noting that the authority of the early Church explicitly rejected the notion of a creation by the Son of God.

3.2 The First Council of Constantinople (381)

With this second ecumenical council, we leave behind the controversy over the divinity of Christ and enter the controversy over the divinity of the Holy Spirit. The opposition between the Arians (supporters of Arius’ theology) and the Nicenes (faithful to the faith of the Council of Nicaea) had not disappeared, and Basil of Caesarea, known as “the Great”, defended the Nicene faith against the Arians by developing the theology of the Trinity. Following Origen, a synod convened by Athanasius in Alexandria in 362 proposed that God should have a single “essence” (“ousia”) but three distinct “hypostases” (contrary to the use of the term in the Nicene symbol). A controversy then broke out with the “pneumatomatics”, who denied the divinity of the Holy Spirit, although they were not opposed to the Nicene faith. It was the accession of Theodosius I, known as “the Great”, as Eastern Roman Emperor (first), that brought the discussion to the First Council of Constantinople, which he convened after professing the Nicene faith and condemning Arianism, and with a view to promoting unity on this issue. The council began in 381, and was presided over first by Melèce of Antioch, then by Gregory of Nazianzus after his death, both friends of Basil of Caesarea, who had already died. Only Eastern bishops were invited, while the anti-Nicene bishops were not allowed to attend and the pneumatomatics refused to participate. Gregory of Nazianzus resigned before the end, but the Council decided the question of the Holy Spirit, affirming his “lordship”, his procession from the Father and his equal dignity with the Father and the Son. The Nicaea symbol was significantly modified and expanded to incorporate these conclusions, in the form recognised as the Nicaea-Constantinople symbol, the translation of which we are also reproducing:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, born of the Father before all ages, light of light, true God of true God; begotten and not made, consubstantial with the Father, through whom all things were made; who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, became incarnate through the Holy Spirit, of the Virgin Mary, and became man ; who was also crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, suffered, was buried and rose again on the third day, according to the Scriptures; who ascended into heaven, is seated at the right hand of God the Father, from where he will come with glory to judge the living and the dead; whose reign will have no end. We believe in the Holy Spirit, Lord and life-giver, who proceeds from the Father and is to be worshipped and glorified with the Father and the Son, who spoke through the holy prophets.

The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed (Wikipedia, 22/09/2022)

Note the clarification on the incarnation of Christ: it is the Holy Spirit who is here explicitly designated as the agent of the miracle, he who is also here called Lord, a title reserved in the Scriptures for God and attributed in the New Testament to Jesus Christ. That the Holy Spirit “proceeds” from the Father underlines his identity of essence with him, and therefore also with the Son. But the Nicene identification between “essence” and “hypostasis” disappeared, and the second term was used again to distinguish the different “persons” in God, leading to the stable Christological formulations of the Council of Chalcedon (451). We will return to these developments in Trinitarian doctrine when we address the questions of the incarnation of Jesus Christ and the hypostatic union.

0 Comments