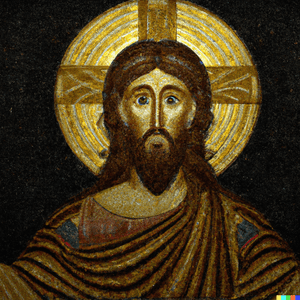

Where does the idea that Jesus is the “incarnation of God” come from? A look at some elements of ancient theology

Introduction

When you attend a church, whatever its denomination, you don’t often wonder about the origin of the statements it professes and in which you believe. Yet the ‘dogmas’ of the Christian churches have a complex history, even though they are thought to be found directly in Scripture. This is the case with the dogma of the incarnation of the Son of God, according to which Jesus Christ is God himself made man, and whose historical constitution and relationship to the Trinitarian doctrine we wish to clarify here.

1.The outline of the doctrine of Christ in the ancient ecumenical councils

The ‘classical’ position on the identity of Jesus Christ, as expressed in the ecumenical councils of Nicaea, Constantinople and Chalcedon (gatherings of the ancient Church to discuss questions of theology and practice), is that Jesus Christ is the incarnation of God the Son. Roughly speaking, according to this historical approach, this means that God is one in nature or substance, but subsists in himself according to three distinct “modalities” (the term is anachronistic) or persons, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ is the incarnation of the Son, i.e. of one of these persons, thus uniting in himself the two natures, divine and human. Thus, in God we would have a single nature in three persons, and in Jesus Christ two natures in a single person.

2.The begetting and incarnation of the Son in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan creed

Let’s explain a little further: the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, formulated at the Councils of Nicea (325) and Constantinople (381) in the context of the Arian controversy (provoked by the presbyter Arius), clarifies the ancient theology in terms of Trinitarian doctrine by affirming that God subsists in himself in three distinct persons or hypostases (the Greek term used in the symbol), the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. The three fully ‘possess’ the one divine substance (hence the term ‘consubstantial’ applied to the Son), without being confused, and the Son is begotten by the Father, these considerations being developed prior to the incarnation in the symbol. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between begetting and incarnation, the first term belonging to the person of the Son in his divine life, the second term designating the coming of the Son in the man Jesus.

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Creator of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, begotten of the Father, that is, of the substance of the Father. God from God, light from light, true God from true God; begotten and not made, consubstantial with the Father; through whom all things were made in heaven and on earth. Who, for us men and for our salvation, came down from heaven, became incarnate and was made man; suffered, rose again on the third day, ascended into heaven, and will come to judge the living and the dead. And to the Holy Spirit.

Creed of Nicaea-Constantinople (Wikipedia, 29/01/2022)

The Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematises those who say: there was a time when he was not: before he was born he was not; he was taken from nothing; he is of a different substance (hypostasis), of a different essence (ousia); he was created; the Son of God is mutable and subject to change.

3.The Chalcedonian Creed and the doctrine of “hypostatic union”: two natures united in one person

The Chalcedonian Creed, formulated at the Council of 451 in the context of the controversy over monophysism (the affirmation of a single ‘nature’ in Christ), clarifies the ancient theology in terms of Christology by clarifying the notion of ‘hypostasis’, which had caused much confusion because of its conceptual affinity with the notion of ‘substance’ (a problem absent from the Latin notion of ‘person’). The Chalcedonian hypostasis is now the “person”, distinguished from the divine “substance”. The Council thus formulated the doctrine of hypostatic union, according to which in Jesus Christ there is union (without confusion) of the two natures (or substances), divine and human, in a single person, the Son, thus clarifying the Nicene-Constantinopolitan formulation of the Incarnation.

Following the holy Fathers, then, we all unanimously teach that we confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in divinity, and the same perfect in humanity, the same truly God and truly man (composed of) a reasonable soul and a body, consubstantial with the Father in divinity and the same consubstantial with us in humanity, in all respects like us except in sin, before the ages begotten of the Father in divinity, and in the last days the same (begotten) for us and for our salvation of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God according to humanity, one and the same Christ, Son of the Lord, the only begotten, recognised in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division and without separation, the difference of the two natures not being in any way abolished by reason of the union, the property of the one and the other nature being rather safeguarded and contributing to one single person and one single hypostasis, a Christ neither splitting nor dividing into two persons, but into one and the same Son, only begotten, God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ.

Chalcedonian Creed (Wikipedia, 29/01/2022)

Conclusion

A large majority of Christian denominations adopt this Trinitarian conception of God and Jesus Christ, whose incarnation is then understood as the assumption (from the verb “to assume”), by the person of the Son of God, of human nature in space and time, without loss of his divine nature outside space and time.

0 Comments